Millbank prison

Millbank Westminster London

MILLBANK PENITENTIARY WALK

Updated March 2019

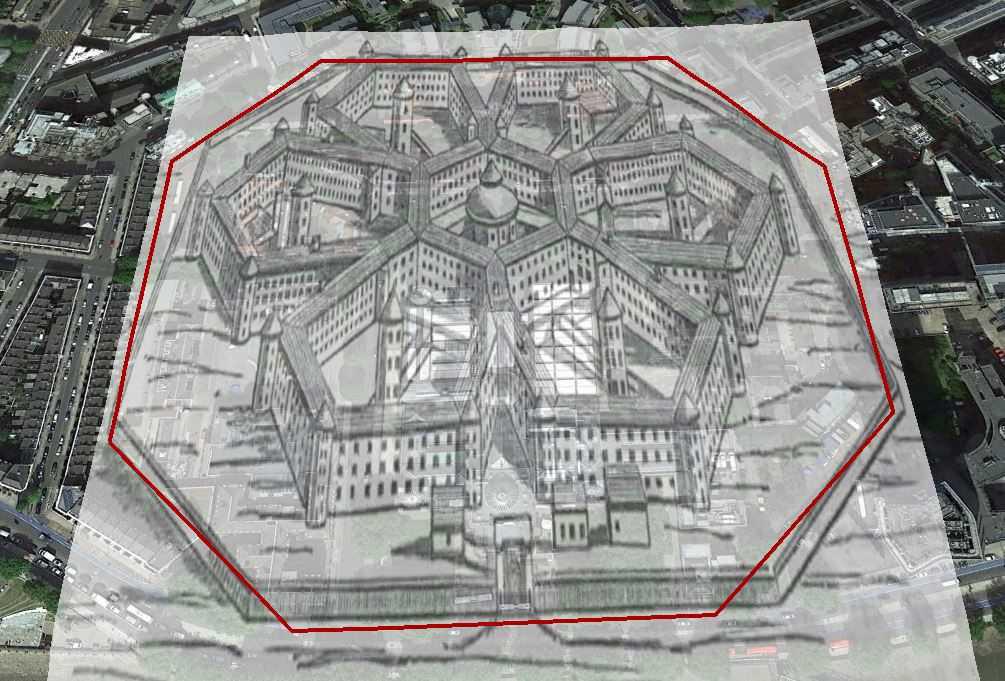

A photo of Millbank Penitentiary, taken from a balloon in 1891

GETTING THERE

The walk commences at the Tate Britain Gallery, Millbank, London, SW1P 4RG. Get there by catching the London Underground to Pimlico Station which is on the Victoria line. It is about a 10 minute walk to the Tate Gallery (follow the signs as you exit the station). From the main entrance of the gallery locate the Tate timeline exhibition on the basement level.

MAP OF THE WALK

STOPS ON THE WALK

Below is an aerial view showing the stops you will make on the walk

The walk will take between 90 and 160 minutes and average around the 2 hour mark. There are 9 stops – roughly 5 mins walk between stops and 5-10 minutes at each stop.

STOP 1

In the basement of the Tate look at the timeline of the Tate Gallery site which indicates that originally this area was a swampy uninhabited part of London called Tothill Fields.

The spot was deemed suitable and business proceeded in June 1812. Due to rising crime in the capital a new prison was required to house men and women convicted of criminal behaviour. At the time convicts were kept in large overcrowded prisons or on the prison hulks in the Thames – usually where the most hardened criminals were kept and put to hard labour.

Plans for a new prison were requested. A prison was built on the site in the early part of the 19th Century – serving first as a model prison following Jeremy Bentham's panopticon design. Bentham published his “Panopticon, or Inspection House idea for a prison in 1791.

The final winning design for the penitentiary, based on the panopticon but deviating slightly, was by Mr William Williams. The first convicts arrived (36 females) on 27th June 1816 and at end of 1820 numbers had risen to 551. The aim was to house over 800 prisoners.

The prison closed in the mid 1820’s due to the poor health of inmates (an outbreak of cholera) and reopened with a different penal role – as a depot for convicts transported to Australia. The penitentiary was in existence from 1816 right through to the 1890’s when the Tate Britain Gallery was erected.

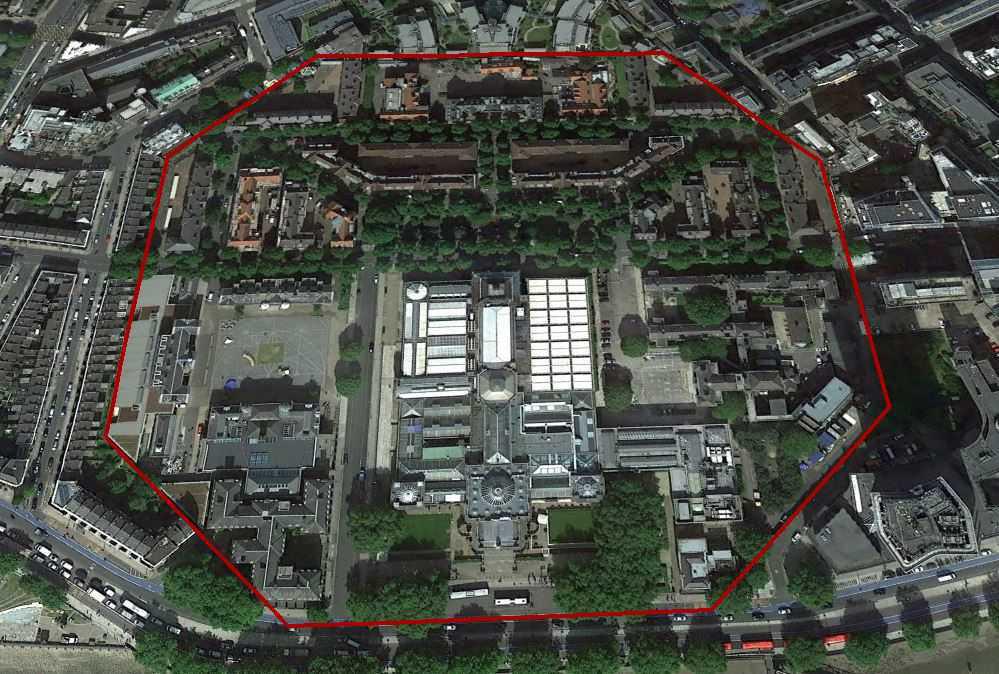

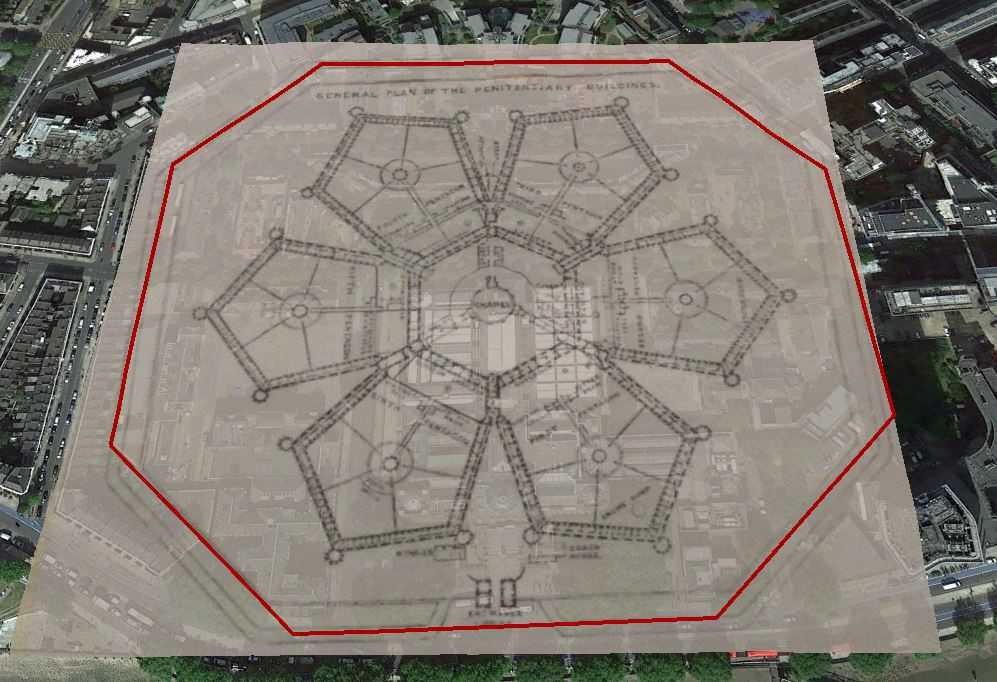

Following are three aerial views of the Tate site. They show the outline of the old penitentiary wall, the plan of the prison and a three-dimensional representation of the buildings.

Outline of the Millbank Penitentiary wall.

The plan of the penitentiary

A 3-D representation of the penitentiary

[Turn left out of the gallery entrance and walk along Millbank away from Vauxhall Bridge. Stop at the first sight of the wall on your left-hand side- 5 mins]

STOP 2

Travelling in an anti-clockwise direction this is the first view of the penitentiary wall.

Building the wall commenced in 1812 and is described as follows in the Supervisor’s minute book: ‘Boundary wall, 17ft high from ground level and 10ft below at a cost of £10,500 (equivalent to £842,000 today)’

The white section may have been a more recent addition, but it is in line with the original wall which can be viewed further along.

The white section of the wall

What was inside the boundary wall?

On maps

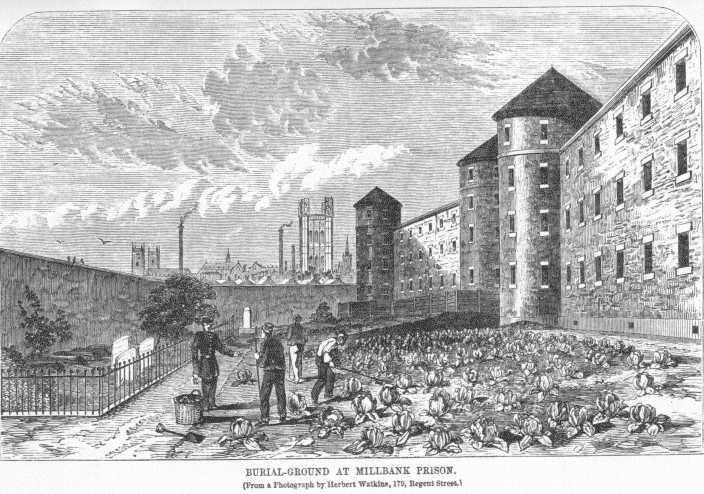

The "Penitentiary" on old London maps looks like a six-pointed star-fort. The central point is the chapel, a circular building which, with the open space around it, covers more than an acre of ground. A narrow building, three stories high, and forming a hexagon, surrounds the chapel, with which it is connected at three points by covered passages. This chapel and its annular belt, the hexagon, forms the omphalos of the whole system. It is the centre of the circle, from which the several bastions of the star-fort radiate. Each of these salients is in shape of a pentagon, and there are six of them, one opposite each side of the hexagon. They are built three storeys high, on four sides of the pentagon, having a small tower at each external angle; while the fifth side of a wall about nine feet high runs parallel to the adjacent hexagon. In these pentagons are the prisoner's cells, while the inner spaces in each, in area about two-thirds of an acre, contain the airing yards, grouped round a tall central watch-tower. The ends of the pentagons join the hexagons at certain points called junctions. The whole space covered by these buildings has been estimated at about seven acres; and something more than that amount is included between them and the boundary wall, which takes the shape of an octagon, and beyond which was a moat now filled up.’ Griffiths p.26

[Walk to the next stop by continuing along Millbank and then entering the Millbank Centre, passing into the garden at the rear, stopping where there are seats - 5 mins] Note there is security here and you will need to ask to enter the gardens.

An old map of London showing the floral design of the prison

STOP 3

Here you can see the wall at its best – it is well preserved and you can see the change in angle from the 1st diagonal to the next straight section following the octagonal shape. You can also clearly see the buttresses along the wall as well as a depression in front of the wall which could have been the moat.

The prison has a chequered history – often condemned but was still surviving in 1877 when it became the only female prison in London – it was the sole reformatory for promising criminals, the first receptacle for military prisoners, the great depot for convicts en route to the Antipodes.

[Walk out of Millbank Centre and bear left going past Pizza Express. Turn sharp left along Thomey Street, continue through City Cafe Walkway to Abell House then turn left along John Islip Street and stop just before the Tate NE gate of the Tate - 5 mins]

STOP 4

Here you can view the wall from inside the Tate entrance and also as it continues on the other side of the John Islip Street.

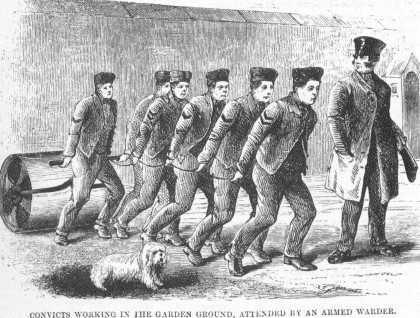

Conditions for prisoners

The convicts were subject to the Silent System with no talking allowed. Discipline at the prison was based on the principle of constant inspection and regular employment. Solitary imprisonment was not common, confinement in a punishment cell being reserved for misconduct. Rewards were given for good behaviour – e.g. badges which could give advantages during transportation. Early release was possible for good behaviour; however, prison life became stricter after the 1860’s.

[Walk through housing estate to Erasmus Street and then turn left along the street. Enter housing estate at Gainsborough House to view continuation of diagonal wall leading to the rear boundary wall. Sit at seats half way along – 5 mins]

STOP 5

Here the wall is a little less clear as it negotiates new buildings – Were the bricks of the penitentiary used in building the estate you see around you? Or were they used to build the school?

Originally constructed to provide working class flats for 4,430 people, Millbank Estate was a flagship project in many ways. Unlike earlier large housing projects, it had no shared lavatories or sculleries, and more spacious courtyards than were to be found in the more affluent mansion blocks in Victoria. Its general appearance dates to the 1930’s following extensive renovation following a large Thames flood. Otherwise it dates from the late 1890’s and early 20th century when the penitentiary was demolished.

There appear to be new sections of the wall and some sections may have been moved – but you can still trace the line of the wall. Note the old gate to the left of the Millbank Estate management building – was this part of the original penitentiary? Some maps appear to mark an entrance here. We will walk along Erasmus Street glimpsing the back wall as it runs parallel to the street behind newer buildings.

[Walk along Erasmus Street and then enter housing estate to trace the line of the wall along the near edge of children’s playground- 5 mins]

“On the whole, as a real system of punishment it (transportation) has failed; as a real system of reform it has failed, as perhaps would every other plan: but as a means of making men outwardly honest; of converting vagabonds most useless in one country, into active citizens in another, and thus giving birth to a new and splendid country, a grand centre of civilisation, it has succeeded to a degree perhaps unparalleled in history.” p.242, Darwin’s Voyage of the Beagle.

STOP 6

Here we can see the clearest remains of the moat which was built outside the wall of the penitentiary. The main boundary wall was surrounded by a ditch or moat which at some point in time became filled – but we can see the original structure here.

View of the moat looking south

View of the moat looking north-west

This is now a community garden and an area where washing is hung out.

Can you imagine what it would have been like to be facing the journey to Australia?

One governor of the prison – Governor Nihil – had to deal with the deportment of an inmate called Pickard Smith, who seemed more than a match for all the authority of the place.

He was known for notorious misconduct but after one re-committal he expressed a desire to be sent abroad. He wrote the following on the back of his cell door:

“London is the place where I was bred and born, Newgate has been too often my situation, The Penitentiary has been too often my dwelling place, And New South Wales is my expectation”

Griffiths p.174

[Walk along the moat to the road and view the wall continuing on the other side of the street – 5 mins] [Question: Is this the main wall or the wall of the outside of the moat?]

STOP 7

Stop within the housing estate. Across the road you can see that the penitentiary wall becomes the back wall of properties along Ponsonby Place.

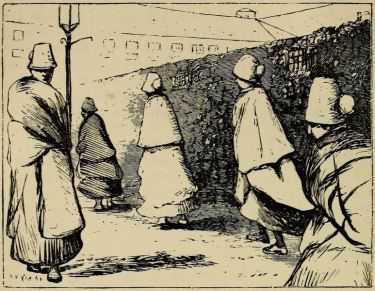

This is most likely the outer wall of the moat surrounding the main wall as it continues from the remaining section of moat wall. The houses along Ponsonby Place were built in the mid-19th Century so existed at the time the penitentiary was in operation. These pictures show how male and female prisoners at Millbank were dressed.

[Walk along Ponsonby Place and cross Millbank to enter Riverside Walk Gardens – 5 mins]

STOP 8

View interpretive board and bollard where transfer boats were moored to take convicts to the ships headed for Australia.

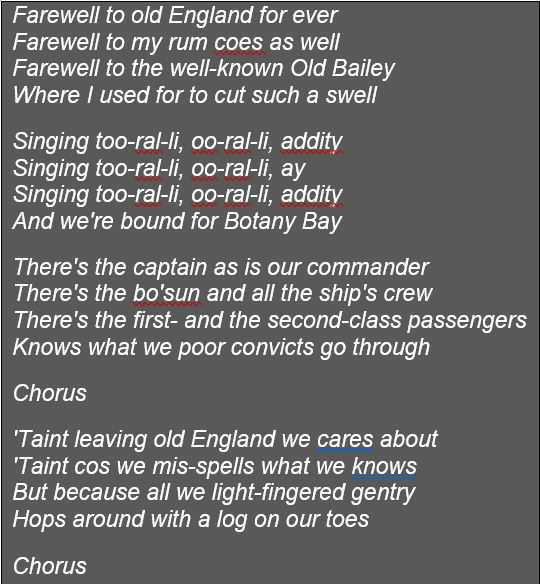

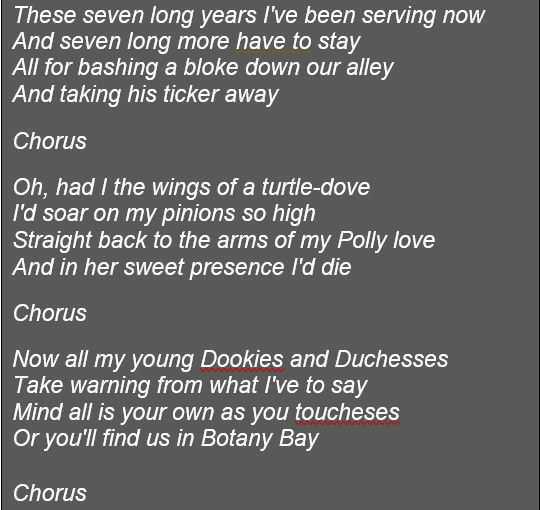

Let’s end with a song and say farewell:

Check out the song –here

[Now it is off to the Morpeth Arms – 5 mins]

STOP 9

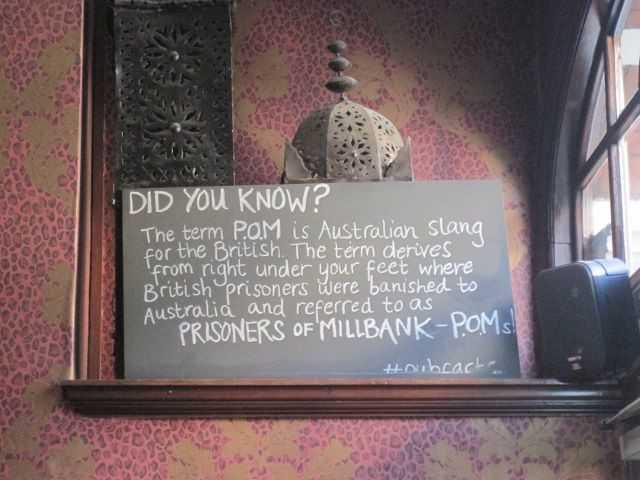

View board about POM explanation – Prisoner of Millbank. Is there any evidence for this? Most explanations of POM refer to the origin being from the acronym of Prisoner of Her Majesty. Also, POM refers to the ruddy (apple like) cheeks of British and Irish convicts. There does not appear to be any hard evidence for Prisoner of Millbank (PoM) being the origin.

View also the claim that cells below are haunted. Note live feed to ‘cells’ via a ‘ghost’ cam.

What was the role of the Millbank penitentiary in shaping the identity of Australia as a nation? The focus of this walk has been on intangible heritage: – graffiti on the back of a cell door, folk ballads and a convict love token. There would be much more about the origins of expressions (particularly slang) now in usage in Australia, the attitude towards authority, The Australian optimistic, ‘can-do’ attitude. There would be jokes which stem from this time.

Australia’s convict history undoubtedly played a part in shaping the nation. Statistics support this.

‘When convict transportation finally ended in 1868 the population of Australia stood at around one million, and approximately 162,000 convicts had been transported in the previous eighty years. These men and women had been the backbone of the new colony, doing the majority of physical labour even after free settlers began to arrive in 1816. Convict transportation only ended when the free population was considered large enough to support the growth and continuing prosperity of the new nation. Without the convicts Australia could not have developed at the rate it did.’

Finish with a well-deserved drink (this can include a cup of tea!)

Link to website of hotel – here

Check out what the view from across the river would have looked like

| END OF WALK – Well done! |